![]()

Lisa Wingate has followed her bestseller, Before We Were Yours with The Book of Lost Friends.

Lost Friends is written in two converging story lines; staged first in a poverty riddled Louisiana school room in 1987 and alternates with an intensely emotional story set around a decaying Louisiana plantation during the Reconstruction period in 1875. It is not a happy story, the Civil War is over and the southern states are in turmoil. But it is an easy read and makes you think about the plight of women and people of color during this lawless period of time in our history.

Louisiana, 1987

“Bennie” Silva, a new college graduate, has accepted a teaching position at a poor rural Louisiana school in exchange for clearing her student debt. She finds the kids mired in poverty and without purpose beyond survival. Most see no purpose to learn about a world that has no interest in them and a different future they can’t even image much less strive to reach.

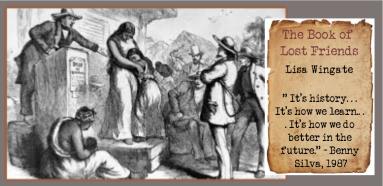

Bennie discovers a book filled with crumbling newspaper articles written by emancipated slaves and published in the Southwestern Christian Advocate. Each article a desperate plea for help in locating family members ripped apart by the auction block. This discovery becomes the catalyst to encourage Bennie’s students to learn of their own legacy and take pride in the part they play in passing that legacy on to the next generation.

Bennie discovers a book filled with crumbling newspaper articles written by emancipated slaves and published in the Southwestern Christian Advocate. Each article a desperate plea for help in locating family members ripped apart by the auction block. This discovery becomes the catalyst to encourage Bennie’s students to learn of their own legacy and take pride in the part they play in passing that legacy on to the next generation.

Louisiana, 1875

Hannie Gossett was born a slave. In the years leading up to the Civil War, her Master, hoping to avoid the prospect of losing control of his “slave property” through emancipation, sent all of Hannie’s extended family west to Texas where he hoped to establish a new plantation. The man overseeing the movement of the slaves sold them off one by one between Louisiana and Texas and absconded with the money. Hannie, at six years old, was the only slave from her family recovered and returned to Louisiana by the Master. She remembers that terrible time and dutifully wears her three blue beads Mama gave each family member so they might recognize each other in a chance meeting in the future.

Every chance there is, Mama says . . .[remember] who’s been carried away from us, and what’s the names of the buyers that took them from the auction block and where’re they gone to. ‘Hardy at Big Creek, to a man name LeBas from Woodville, Het at Jatt carried off by a man name Palmer from Big Woods….’

It’s now 1875. The war is over. Master Gossett is now called Mister Gossett. Missus Gossett remains a feared cruel tyrant. The Gossett’s son, a chip off his mother’s slimy block, is in serious legal trouble out west and his father has left Louisiana for Texas to rescue him. Their daughter, Lavinia, now a young teenager, is a spoiled hate-filled brat, and much to everyone’s relief, has been shipped off to a boarding school. And Mister Gossett has a not-so-secret on-going relationship with a Creole woman that has produced his much loved mixed-race daughter, Juneau Jane. Talk about an dysfunctional family!

It’s 1875. The slaves have been “liberated” and have become sharecroppers with signed land contracts set to mature in the near future. Hannie is now eighteen-years-old and concerned for her future; distrustful of the Gossetts’ honoring the land contracts.

Mister Gossett, as stated, was en-route to Texas to rescue his son and has not been heard from for over four months. Ol’ Tati, caretaker to all the “stray children”, sends Hannie in the dark of night, disguised as a yard-boy to the big house to find their land contracts before the Missus can destroy them in the Mister’s absence.

Hannie is shocked by what she discovers when she arrives at the big house. Lavinia is home from boarding school and working with her mortal enemy, Juneau Jane, to find their father’s will and business papers! Failing to find them, Lavinia furiously orders a carriage driver to take her and Juneau Jane to see her father’s business partner. Hannie spotting a chance to find out what these two are planning, taking a chance she won’t be recognized in her disguise, drives the two half-sisters for what she believes will be a short drive to the partner’s office.

That’s it! All you are going to get from me. I’ll leave you with a clue to the book’s title. Hannie, Juneau Jane and Lavinia travel on a long dangerous and complicated journey. They seek refuge one night in an old building. They find the walls wallpapered with newspapers articles from the Southwestern Christian Advocate newspaper. Hannie is shocked to learn the articles were written by former slaves looking for lost kin.

That’s it! All you are going to get from me. I’ll leave you with a clue to the book’s title. Hannie, Juneau Jane and Lavinia travel on a long dangerous and complicated journey. They seek refuge one night in an old building. They find the walls wallpapered with newspapers articles from the Southwestern Christian Advocate newspaper. Hannie is shocked to learn the articles were written by former slaves looking for lost kin.

NOTE:

The Southwestern Christian Advocate newspaper actually published a Lost Friends column beginning in 1877 and continued for over twenty years. The author based Hannie, Lavinia, and Juneau Jane on an article written by a former slave named Caroline Flowers.

I met Ona Judge Staines in the archives. . . I was conducting research. . . about nineteenth-century black women in Philadelphia and I came across an advertisement about a runaway slave. . . called “Oney Judge”. She had escaped from the President’s House. . . How could it be that I never heard of this woman. (Erica Armstrong Dunbar)

I met Ona Judge Staines in the archives. . . I was conducting research. . . about nineteenth-century black women in Philadelphia and I came across an advertisement about a runaway slave. . . called “Oney Judge”. She had escaped from the President’s House. . . How could it be that I never heard of this woman. (Erica Armstrong Dunbar) George Washington was reputed to be a “kinder” slave owner which meant he fed and provided for his slaves somewhat better than others. His hot-temper has been sanitized in history and ask the slaves that were housed in the smoke house in the new capital if they had five-star accommodations.

George Washington was reputed to be a “kinder” slave owner which meant he fed and provided for his slaves somewhat better than others. His hot-temper has been sanitized in history and ask the slaves that were housed in the smoke house in the new capital if they had five-star accommodations. She learned the truth about her place in their lives when the national capital moved to Philadelphia. Pennsylvania law “required emancipation of all adult slaves who were brought into the commonwealth for more than a period of six months.” The President, financially strapped back on the plantation feared the lost property value of freed slaves. To protect his investments, Washington devised a shifty system of uprooting his Philadelphia slaves and rotating back to Mount Vernon before the six months deadline.

She learned the truth about her place in their lives when the national capital moved to Philadelphia. Pennsylvania law “required emancipation of all adult slaves who were brought into the commonwealth for more than a period of six months.” The President, financially strapped back on the plantation feared the lost property value of freed slaves. To protect his investments, Washington devised a shifty system of uprooting his Philadelphia slaves and rotating back to Mount Vernon before the six months deadline. Shortly before her death February 25, 1848, Ona, nearly 80 years old and still a fugitive slave of the Custis estate, gave interviews with two abolitionists newspapers. Both interviews appear in the appendix. They are believed to be a unique opportunity to view life as a slave in the Washington presidency.

Shortly before her death February 25, 1848, Ona, nearly 80 years old and still a fugitive slave of the Custis estate, gave interviews with two abolitionists newspapers. Both interviews appear in the appendix. They are believed to be a unique opportunity to view life as a slave in the Washington presidency. cond Mrs. Hockaday

cond Mrs. Hockaday