![]()

![]()

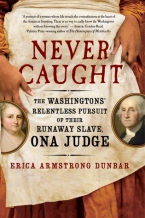

In January of 2018, a review of a new book featuring George Washington and his runaway slave named Ona “Oney” Judge caught my attention. I picked up a copy to review for Black History Month in 2019.

NEVER CAUGHT – The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave Ona Judge is a narrative non-fiction. The book is heavily footnoted and supplemented with a lengthy bibliography and index. In a twist from most historical works on Washington that focus on his evolving beliefs about the concept of slavery, Never Caught flips the script. Erica Armstrong Dunbar examines what it means to be born a free person into a world where you are trapped in slavery. A world where every effort is taken to strip you of your humanity and rights as a human being. In narrating the unearthed facts of Ona Judge Staines life, Dunbar exposes the raw facts of slavery -man’s inhumanity against man.

I met Ona Judge Staines in the archives. . . I was conducting research. . . about nineteenth-century black women in Philadelphia and I came across an advertisement about a runaway slave. . . called “Oney Judge”. She had escaped from the President’s House. . . How could it be that I never heard of this woman. (Erica Armstrong Dunbar)

Quick. Tell me the first ten things that come to mind about the first president of the United States of America. Bet they include: He was married to Martha. Lived in Mount Vernon, Virginia. Had false teeth (ivory not wood). Was trained as a surveyor. Fought in the American Revolution. Became our first President. Never lived in Washington D.C. because it didn’t exist in his lifetime. Never told a lie (that is a lie). Served two terms in office. We celebrate a national holiday on his birthday.

What? No mention that George at the tender age of eleven, following his father’s untimely death, inherited a 280-acre farm with ten slaves? By the time he married Martha, he personally owned over 100 slaves. Martha Parke Custis, widow of Daniel Park Custis, brought 84 dower slaves from the Custis estate to Mount Vernon upon her marriage. Dower slaves are part of an estate and can only be inherited by members of that estate. George and Martha controlled them but did not own them and could not set them free. Upon Martha’s death, the dower slaves would be passed along like fine china or an heirloom chair to living members of the Custis estate.

George Washington was reputed to be a “kinder” slave owner which meant he fed and provided for his slaves somewhat better than others. His hot-temper has been sanitized in history and ask the slaves that were housed in the smoke house in the new capital if they had five-star accommodations.

George Washington was reputed to be a “kinder” slave owner which meant he fed and provided for his slaves somewhat better than others. His hot-temper has been sanitized in history and ask the slaves that were housed in the smoke house in the new capital if they had five-star accommodations.

A favorite dower slave of Martha’s, known only as Mulatto Betty, gave birth in 1773 to a daughter named Ona Marie and fathered by Andrew Judge, a white indentured servant. Ona’s “carefree” childhood ended when she was nine years old. She was sent to work full-time in the mansion to become Martha Washington’s personal servant and to receive training as a seamstress from her mother. She excelled at both tasks earning her a “most favored slave” status.

As our first President-elect headed north to New York and the nation’s new capital, he knew slavery laws in the northern states were unraveling; the early smells of manumission and freedom floating in the air. He hand-picked slaves he thought he could trust not to run away if they learned that freedom was a possibility – Ona Judge, now in her teens, was high on that list.

Ona played her part carefully. She yearned for freedom. Yearned for a life where her safety and well being wasn’t subjected to the whims of a trigger tempered slave owner. For safeties sake she outwardly projected submission and affection for the Washington family; a family riddled with grief, misery, and poor health. Perhaps in some way she believed the Washington’s had special feelings for her; they did allow her more liberties to travel within the northern city unaccompanied. It is more likely allowing her to dress nicely was meant to reflect more on their social status than on her well-being.

She learned the truth about her place in their lives when the national capital moved to Philadelphia. Pennsylvania law “required emancipation of all adult slaves who were brought into the commonwealth for more than a period of six months.” The President, financially strapped back on the plantation feared the lost property value of freed slaves. To protect his investments, Washington devised a shifty system of uprooting his Philadelphia slaves and rotating back to Mount Vernon before the six months deadline.

She learned the truth about her place in their lives when the national capital moved to Philadelphia. Pennsylvania law “required emancipation of all adult slaves who were brought into the commonwealth for more than a period of six months.” The President, financially strapped back on the plantation feared the lost property value of freed slaves. To protect his investments, Washington devised a shifty system of uprooting his Philadelphia slaves and rotating back to Mount Vernon before the six months deadline.

What the others thought about their repeatedly uprooted lives we do not know. We do know that Ona knew of the progress toward freedom around her. She guardedly watched for that one split second in time where she could chance leaving. When Ona learned that she would be given as a wedding present to Washington’s volatile granddaughter during the next rotation back to Virginia, she knew it was now or never. Taking her life in her hands, she reached out to the free blacks in Philadelphia for help and fled. Ona, now twenty-two-years old and illiterate, headed out into the scary world alone as a fugitive willing to face death or capture.

Her harrowing journey took her to Portsmouth, New Hampshire. She found menial labor and despite the back breaking work, enjoyed her veiled freedom. One can only imagine the horror she felt the day she was recognized on the street by a friend of Washington. Once notified she had been located, Washington put on a full court press, illegally using the power of his office, to have a local government official convince her to return of her own volition. After failing at that attempt, Washington repeatedly sought to locate and physically return her. His tiny slave outwitted him at every turn.

Ona fled to Greenland, New Hampshire and stayed out of the grasp of capture for over fifty years. She married, had children, kept a low profile and missed her biological family still back at Mount Vernon.

Shortly before her death February 25, 1848, Ona, nearly 80 years old and still a fugitive slave of the Custis estate, gave interviews with two abolitionists newspapers. Both interviews appear in the appendix. They are believed to be a unique opportunity to view life as a slave in the Washington presidency.

Shortly before her death February 25, 1848, Ona, nearly 80 years old and still a fugitive slave of the Custis estate, gave interviews with two abolitionists newspapers. Both interviews appear in the appendix. They are believed to be a unique opportunity to view life as a slave in the Washington presidency.

“When asked if she is not sorry she left Washington, as she has labored so much harder since, than before, her reply is ‘No, I am free, and I have, I trust, been made a child of God by the means‘”.

Highly recommend reading for young adults and those interested in history. A chance to look behind the curtains of the first First Family. A chance to learn about a young black woman determined to be remembered – a human being and a child of God.

John and Ella Robina have shared a wonderful life for more than fifty years. Now in their eighties, Ella suffers from cancer and has chosen to stop treatment. John has Alzheimer’s.

John and Ella Robina have shared a wonderful life for more than fifty years. Now in their eighties, Ella suffers from cancer and has chosen to stop treatment. John has Alzheimer’s.  Yearning for one last adventure, the self-proclaimed “down-on-their-luck geezers” kidnap themselves from the adult children and doctors who seem to run their lives to steal away from their home in suburban Detroit on a forbidden vacation of rediscovery.

Yearning for one last adventure, the self-proclaimed “down-on-their-luck geezers” kidnap themselves from the adult children and doctors who seem to run their lives to steal away from their home in suburban Detroit on a forbidden vacation of rediscovery. John’s best friend had been warehoused in a nursing home, tethered to life support, terrified, and living the same events over and over in Groundhog Day style. After his friend’s death, John feared, he too, would follow in his friend’s footsteps. He made Ella vow that if the aperture in his own mind closed, she would not leave him staked out to die a lonely and prolonged death in a nursing home.

John’s best friend had been warehoused in a nursing home, tethered to life support, terrified, and living the same events over and over in Groundhog Day style. After his friend’s death, John feared, he too, would follow in his friend’s footsteps. He made Ella vow that if the aperture in his own mind closed, she would not leave him staked out to die a lonely and prolonged death in a nursing home. “While the children are only concerned for our well-being, it’s still really none of their business. Durable power of attorney doesn’t mean you get to run the whole show. . . Is this [trip] a good idea? Don’t be stupid. Of course it’s not a good idea.“

“While the children are only concerned for our well-being, it’s still really none of their business. Durable power of attorney doesn’t mean you get to run the whole show. . . Is this [trip] a good idea? Don’t be stupid. Of course it’s not a good idea.“

Depression era Dorothea Lange image entitled Migrant Mother. After reading Mary Coin, a book I highly recommend and

Depression era Dorothea Lange image entitled Migrant Mother. After reading Mary Coin, a book I highly recommend and  Chapter One. Opening scene. 1964, Berkley, California. If this was a movie script, Dorothea Lange, now elderly and gravely ill, would be seen opening an envelope embossed with the image of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The contents of that letter, we later learn, informs her of their plan for a retrospective exhibit of her life’s work.

Chapter One. Opening scene. 1964, Berkley, California. If this was a movie script, Dorothea Lange, now elderly and gravely ill, would be seen opening an envelope embossed with the image of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The contents of that letter, we later learn, informs her of their plan for a retrospective exhibit of her life’s work. I lean over to open a drawer and retrieve [my] files. California, 1936. New Mexico, 1935. Texas, 1938. Arkansas, 1938, Arizona, 1940. Black-and-white photographs spill out…Faces of men, women, and children… They gave a face to the masses struggling to make ends meet. They started conversations… And while I don’t regret my choices, I am saddened that I’ve hurt people dear to me.

I lean over to open a drawer and retrieve [my] files. California, 1936. New Mexico, 1935. Texas, 1938. Arkansas, 1938, Arizona, 1940. Black-and-white photographs spill out…Faces of men, women, and children… They gave a face to the masses struggling to make ends meet. They started conversations… And while I don’t regret my choices, I am saddened that I’ve hurt people dear to me. The Stock Market Crash in 1929 changed everyone’s future. Her clientele disappeared one-by-one as family portraits become a luxury few could afford. By this time, she had married her first husband, Maynard Dixon, a hot-tempered philandering landscape painter with traveling “genes”. Dorothea, the mother of two boys, found herself between a rock and a hard place. With a floundering marriage and two dependent children, she needed to find work in a world where everyone needed a job. As she struggled to find new footing, Dorothea made the heartbreaking decision to foster-out her boys to give them a stable caring home. A decision made after seeing children left to fend for themselves in the streets.

The Stock Market Crash in 1929 changed everyone’s future. Her clientele disappeared one-by-one as family portraits become a luxury few could afford. By this time, she had married her first husband, Maynard Dixon, a hot-tempered philandering landscape painter with traveling “genes”. Dorothea, the mother of two boys, found herself between a rock and a hard place. With a floundering marriage and two dependent children, she needed to find work in a world where everyone needed a job. As she struggled to find new footing, Dorothea made the heartbreaking decision to foster-out her boys to give them a stable caring home. A decision made after seeing children left to fend for themselves in the streets. This first photo led to twenty years of documenting the lives of the downtrodden with the goal of raising the awareness of their plight to the unaffected. Some of her work proved too revealing. Her photos of the Japanese American relocation camps were confiscated by the government; a nation unwilling to expose its racism against its own citizenry.

This first photo led to twenty years of documenting the lives of the downtrodden with the goal of raising the awareness of their plight to the unaffected. Some of her work proved too revealing. Her photos of the Japanese American relocation camps were confiscated by the government; a nation unwilling to expose its racism against its own citizenry.